To activate navigation with sound select the text.

The singular mining wealth of the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula was one of the main reasons for the Roman conquest, and it also explains the expedition that took place, Décimo Xunio Bruto, nicknamed El Galaico, in 137 BC. Thus, imperial mining (metalla publica), especially that of gold, was the main economic activity of Rome in Gallaecia and Asturia.

The writer, soldier, naturalist and scientist Pliny the Elder (23 AD-79 AD), in his work Naturalis Historia, points out that the mining of gold, tin, iron or lead underwent a radical transformation during the period of Romanization, intensifying its extraction in respect to the previous period, carried out by the Galician indigenous peoples.

Before Romanization the mining of gold was made by the indigenous people who lived in the settlements through the panning on the banks of the rivers.

ROMAN MINING IN THE NORTH WEST

The Roman techniques of gold mining (aurum) were three.

- The washing of the sands by panning of the sand of the rivers, a method used by the Galician natives. For that they used wooden screens and rafts. It is what the Romans called Aurum fluminum.

In the words of Plinio:

"In our world [...] gold It is extracted in three ways: firstly in the particles [or nuggets] from rivers, such as from the Tagus in Hispania [...], and there isn´t a purer gold, because it is polished by the current. It is also extracted in other ways through wells or it is found by knocking down mountains. Let's talk, then, of these two systems [...] "

- The mining of the gold mines by means of trenches wells and underground passages. Known as Aurum canalicium or Canaliense, it is the same as the primary deposits in the rock or mine.

In the words of Plinio :

"The gold that is extracted from the mountains [through mine shafts] called 'canalicium', otherwise known as 'canaliense'; adheres to marble stones [any type of hard rock], not the same as how the sapphire of the East shines or the Thebes and other precious stones, but is wrapped in marble particles [that´s to say it is found scattered through all the rock,] [...] "

- The ruina montium was a technique that was applied in alluvial or secondary gold deposits. It favoured that the force of the water would separate the conglomerates and wash the gold. Pliny also called it Aurum arrugiae -the gold of wrinkles-, that is, the gold obtained by means of the force of water.

In the words of Plinio :

"The third procedure surpasses the work of the Giants; the mountains are mined along a large area through underground passages excavated by lamp light, whose duration allows you to measure shifts and for many months you do not see the light of day. This type of mining is called 'arrugia'. Often shafts are opened, dragging out the miners in the event of a collapse [...] That's why there are numerous stone caves left to support the mountains "

THE ROMAN MINING ADMINISTRATION

The mines were property of the empire and depended on the treasury. In the northwest of the peninsula they were controlled by the procurator Asturiae et Callaeciae, who administered the mines and was based in Asturica Augusta (Astorga).

Between the end of the 1st century AD and the first half of II century AD each mining area also had a Procurator metallorum, which resided in the capital of each mining district.

The Legio VII Gemina ("The Twins' Seventh Legion") formed by 6,000 soldiers and based in the city of León, together with its auxiliary units, was intended to protect and control the extraction and transport of gold from the Northwest.

Constructors and miners

The construction of communication roads and open pit mines had to be controlled by an elite of Roman engineers, a highly specialized technical squad possibly linked to the army.

Augustus, the first Roman emperor (27 BC-14 AD), promotes the abandonment of the pre-Roman settlements and the settlement of the indigenous population in the valleys.

The Roman gold mines were not worked mostly by slaves, but by the local indigenous population who paid their tribute to Rome in the form of working in the mines.

However, slave labor also existed, as well as that of those condemned to forced labor (damnati ad metalla), but the majority would be free individuals of indigenous origin.

The specialized personnel of the mine (engineers, technicians and administrators) lived in a kind of base camp similar to a rural village-factory located near the mine.

Coins

The Romans extracted gold (aurum) and used it mainly to mint coins, although they also made jewellery with that precious metal. The emperor Augusto (27 BC.-14 AD) to strengthen his power, decided to introduce a monetary novelty in the Empire. The main currencies would be the golden Aureus - of gold - and the denarius - of silver - although usually others were also used of bronze or copper.

Besides being used to make purchases, coins in the Roman world were useful as a means of propaganda for the rulers. The origin of Roman mining in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula is explained by the policy of Augustus, who began to coin gold with a propagandistic purpose.

The Roman state extracted from the mines of the peninsular Northwest much of the gold needed to mint the coin for two centuries. The monetary crisis of the third century caused the currencies to change their value and the mines had to be closed.

The Roman mine of As Borreas, also receives the name of As Telleiras, since it was used to extract clay to manufacture tiles in the 1960s.

For more information:

- Xusto Rodríguez, M. Castro territoriality e Galician-Roman in Southeast Galicia: A land of Viana do Bolo. Bulletin Auriense.Anexo 18. Archaeological Museum from Ourense. 1993

- Orejas, A. The work in Las Médulas. Las Médulas Foundation 2002

- Sánchez Palencia, F.J. Las Médulas (León). A cultural landscape in the Asturia Augustana. Leonés Institute of Culture. Lion. 2000

WORK OF GIANTS

Ruina Montium is the ancient Roman mining technique that combines the construction of wells and underground galleries with the use of water to tear down large masses of gold bearing land. The use of hydraulic power made it possible to reduce labor needs, favoring the movement of large amounts of land to a level that was not exceeded until the nineteenth century.

The channeling of water passed down the slope of the mountains thanks to the force of gravity.

The mine was the object of the construction of an important hydraulic infrastructure along several kilometres in the form of artificial water channels or corrugus. After several kilometres the water reached the main deposits, at the head of the farm, from where it was distributed to the montium ruina wells.

Plinio explained it as: "Another analogous and more costly task is to bring water currents to wash these landslides, sometimes from the top of the mountains, often a distance of 100 miles; [...] It is convenient that the slope is calculated, so that, rather than flowing, it runs; and that's why they are brought from the higher areas. "

The Romans were looking for areas rich in mineral resources, especially gold, to exploit them systematically.

The mine occupied an area of about 17 hectares.

For the washing of all the materials coming from the landslides caused by water erosion, it would be necessary to channel them through the agogae, for the sedimentation and decantation of the mineral.

Once in the mine, the water was used to collapse the front of mine face by means of vertical wells and horizontal passages through which the water was stored in the flooded tanks.

The mountain suddenly collapsed with a landslide because of the flood of water

GOLD MINING

Then the conglomerate separated using water jets in the washing and decanting channels, also known as agogae (agogoe). According to Plinio this technique had a very low cost and a very high efficiency.

To avoid the collapse of the panning site and facilitate the drainage of the residual material, four washing containers or alluvial fans were opened in an East-West direction that facilitated their dumping into the river.

The work: The process would consist of directing the water from the mine face through some river beds made manually, dragging the rocks and clay. The action of the miners' picks, which would be placed either on the side of the stream or inside it, would do the rest.

Agogae: They are the pits made in the ground area of the mine to which the water coming from the head of the farm stops. Before the mud swept by the water entered the agogas ( channels for drawing off water) the thicker boulders were removed, which the miners deposited in heaps aligned along the sides of the canals, in areas that had already been mined. Those piles of rocks are called "murias".

Canal of wood: To retain the gold dust, heather was used in a channel through which water flowed with minerals. Plinio says that "the ulex, after drying, burns and its ash is washed by placing it under a bed of grass so that the gold can be felt there". Having a higher density, the gold was deposited in the bottom of the channel, where it was retained by the leaves of heather.

The name of the mine comes from the word "Erase" (lat. Burra), synonym of sediment, waste, in reference to the material left over from the mine.

SETTLEMENTS IN THE AREA OF AS BORREAS

Some researchers believe that the Beneficiarius Procuratoris, together with its garrison, could reside in the village of A Vila da Sen (parish of Bembibre), located 2.5 km southwest of the As Borreas Mine. This hypothesis is based on three indications:

- The geographical proximity of the settlement to the mine and also the perfect visual domain that would exert over it and its accesses.

- The ease of communication between both sites, still retaining the remains of a path and an old way of passage: the Morteira Bridge.

- The appearance in the fort of A Vila da Sen of fragments of common Roman ceramics consisting of imitations of fountains with red-Pompeian varnish.

In order to exercise control over the network of water supply to the mine, it is believed that another garrison could be located at the settlement of A Cabeza de Seoane (Santo Adrao de Solbeira).

.

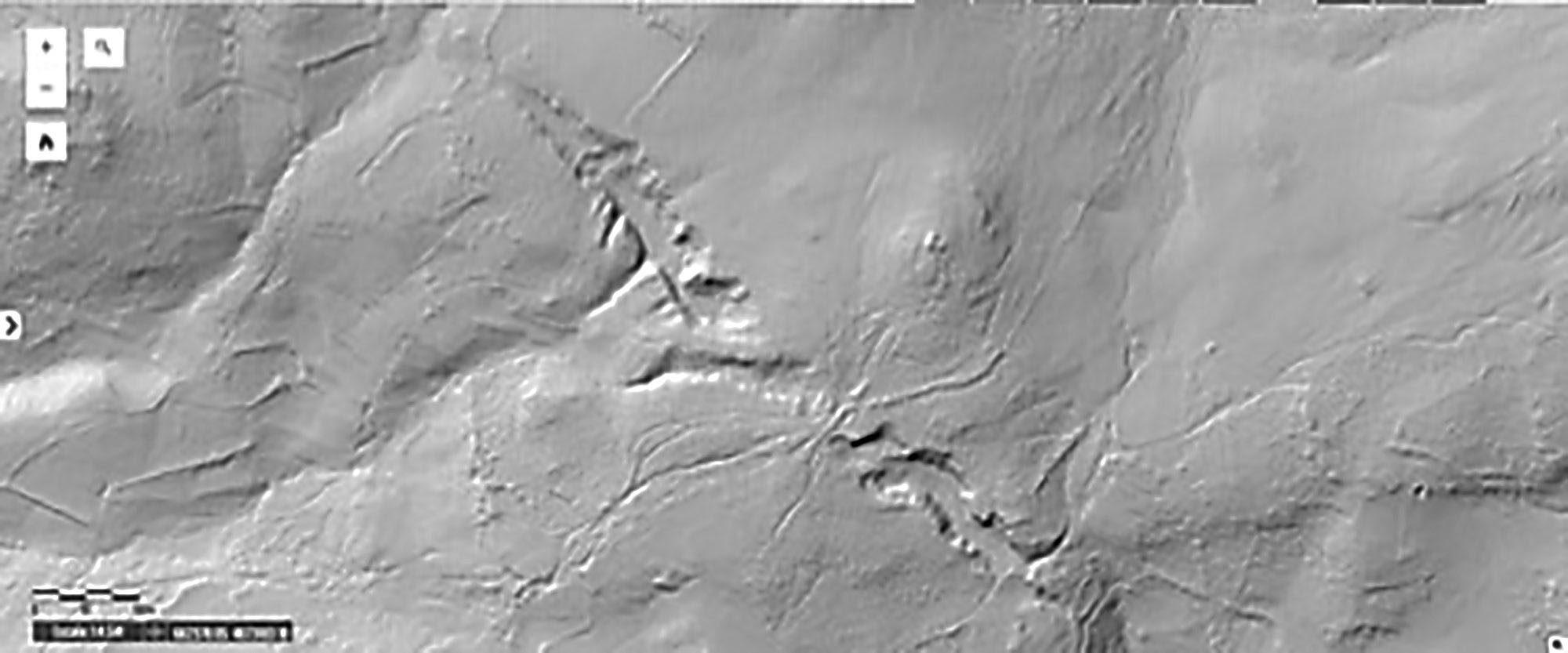

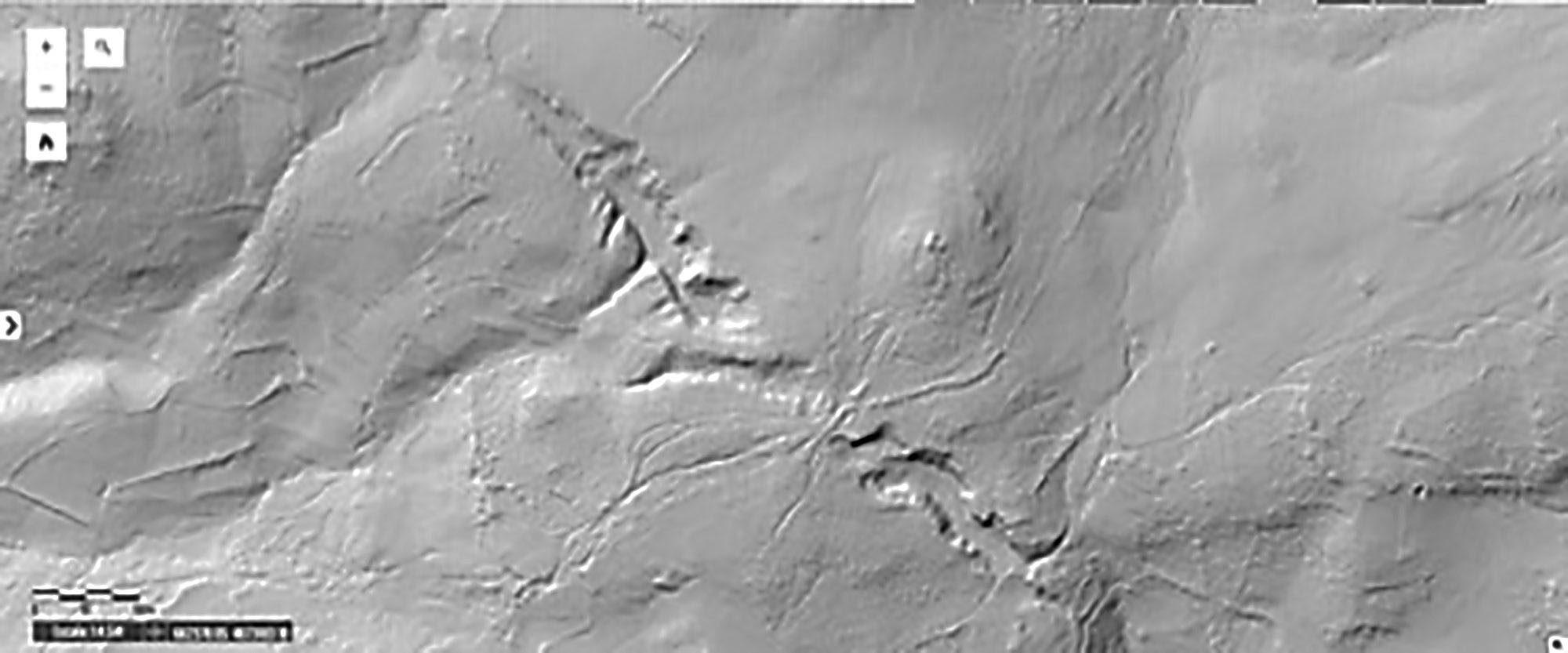

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

Roman low-relief representing a group of miners Discovered near Linares (Jaén) in 1875

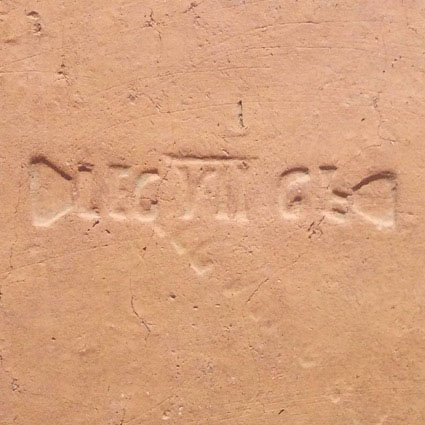

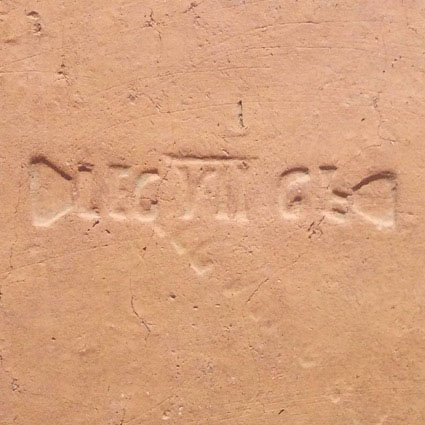

Slate with the mark of the VII Legion

Iron mine peak found in the settlement of Castromao (Celanova)

The singular mining wealth of the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula was one of the main reasons for the Roman conquest, and it also explains the expedition that took place, Décimo Xunio Bruto, nicknamed El Galaico, in 137 BC. Thus, imperial mining (metalla publica), especially that of gold, was the main economic activity of Rome in Gallaecia and Asturia.

The writer, soldier, naturalist and scientist Pliny the Elder (23 AD-79 AD), in his work Naturalis Historia, points out that the mining of gold, tin, iron or lead underwent a radical transformation during the period of Romanization, intensifying its extraction in respect to the previous period, carried out by the Galician indigenous peoples.

Before Romanization the mining of gold was made by the indigenous people who lived in the settlements through the panning on the banks of the rivers.

ROMAN MINING IN THE NORTH WEST

The Roman techniques of gold mining (aurum) were three.

- The washing of the sands by panning of the sand of the rivers, a method used by the Galician natives. For that they used wooden screens and rafts. It is what the Romans called Aurum fluminum.

In the words of Plinio:

"In our world [...] gold It is extracted in three ways: firstly in the particles [or nuggets] from rivers, such as from the Tagus in Hispania [...], and there isn´t a purer gold, because it is polished by the current. It is also extracted in other ways through wells or it is found by knocking down mountains. Let's talk, then, of these two systems [...] "

- The mining of the gold mines by means of trenches wells and underground passages. Known as Aurum canalicium or Canaliense, it is the same as the primary deposits in the rock or mine.

In the words of Plinio :

"The gold that is extracted from the mountains [through mine shafts] called 'canalicium', otherwise known as 'canaliense'; adheres to marble stones [any type of hard rock], not the same as how the sapphire of the East shines or the Thebes and other precious stones, but is wrapped in marble particles [that´s to say it is found scattered through all the rock,] [...] "

- The ruina montium was a technique that was applied in alluvial or secondary gold deposits. It favoured that the force of the water would separate the conglomerates and wash the gold. Pliny also called it Aurum arrugiae -the gold of wrinkles-, that is, the gold obtained by means of the force of water.

In the words of Plinio :

"The third procedure surpasses the work of the Giants; the mountains are mined along a large area through underground passages excavated by lamp light, whose duration allows you to measure shifts and for many months you do not see the light of day. This type of mining is called 'arrugia'. Often shafts are opened, dragging out the miners in the event of a collapse [...] That's why there are numerous stone caves left to support the mountains "

THE ROMAN MINING ADMINISTRATION

The mines were property of the empire and depended on the treasury. In the northwest of the peninsula they were controlled by the procurator Asturiae et Callaeciae, who administered the mines and was based in Asturica Augusta (Astorga).

Between the end of the 1st century AD and the first half of II century AD each mining area also had a Procurator metallorum, which resided in the capital of each mining district.

The Legio VII Gemina ("The Twins' Seventh Legion") formed by 6,000 soldiers and based in the city of León, together with its auxiliary units, was intended to protect and control the extraction and transport of gold from the Northwest.

Constructors and miners

The construction of communication roads and open pit mines had to be controlled by an elite of Roman engineers, a highly specialized technical squad possibly linked to the army.

Augustus, the first Roman emperor (27 BC-14 AD), promotes the abandonment of the pre-Roman settlements and the settlement of the indigenous population in the valleys.

The Roman gold mines were not worked mostly by slaves, but by the local indigenous population who paid their tribute to Rome in the form of working in the mines.

However, slave labor also existed, as well as that of those condemned to forced labor (damnati ad metalla), but the majority would be free individuals of indigenous origin.

The specialized personnel of the mine (engineers, technicians and administrators) lived in a kind of base camp similar to a rural village-factory located near the mine.

Coins

The Romans extracted gold (aurum) and used it mainly to mint coins, although they also made jewellery with that precious metal. The emperor Augusto (27 BC.-14 AD) to strengthen his power, decided to introduce a monetary novelty in the Empire. The main currencies would be the golden Aureus - of gold - and the denarius - of silver - although usually others were also used of bronze or copper.

Besides being used to make purchases, coins in the Roman world were useful as a means of propaganda for the rulers. The origin of Roman mining in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula is explained by the policy of Augustus, who began to coin gold with a propagandistic purpose.

The Roman state extracted from the mines of the peninsular Northwest much of the gold needed to mint the coin for two centuries. The monetary crisis of the third century caused the currencies to change their value and the mines had to be closed.

The Roman mine of As Borreas, also receives the name of As Telleiras, since it was used to extract clay to manufacture tiles in the 1960s.

For more information:

- Xusto Rodríguez, M. Castro territoriality e Galician-Roman in Southeast Galicia: A land of Viana do Bolo. Bulletin Auriense.Anexo 18. Archaeological Museum from Ourense. 1993

- Orejas, A. The work in Las Médulas. Las Médulas Foundation 2002

- Sánchez Palencia, F.J. Las Médulas (León). A cultural landscape in the Asturia Augustana. Leonés Institute of Culture. Lion. 2000

WORK OF GIANTS

Ruina Montium is the ancient Roman mining technique that combines the construction of wells and underground galleries with the use of water to tear down large masses of gold bearing land. The use of hydraulic power made it possible to reduce labor needs, favoring the movement of large amounts of land to a level that was not exceeded until the nineteenth century.

The channeling of water passed down the slope of the mountains thanks to the force of gravity.

The mine was the object of the construction of an important hydraulic infrastructure along several kilometres in the form of artificial water channels or corrugus. After several kilometres the water reached the main deposits, at the head of the farm, from where it was distributed to the montium ruina wells.

Plinio explained it as: "Another analogous and more costly task is to bring water currents to wash these landslides, sometimes from the top of the mountains, often a distance of 100 miles; [...] It is convenient that the slope is calculated, so that, rather than flowing, it runs; and that's why they are brought from the higher areas. "

The Romans were looking for areas rich in mineral resources, especially gold, to exploit them systematically.

The mine occupied an area of about 17 hectares.

For the washing of all the materials coming from the landslides caused by water erosion, it would be necessary to channel them through the agogae, for the sedimentation and decantation of the mineral.

Once in the mine, the water was used to collapse the front of mine face by means of vertical wells and horizontal passages through which the water was stored in the flooded tanks.

The mountain suddenly collapsed with a landslide because of the flood of water

GOLD MINING

Then the conglomerate separated using water jets in the washing and decanting channels, also known as agogae (agogoe). According to Plinio this technique had a very low cost and a very high efficiency.

To avoid the collapse of the panning site and facilitate the drainage of the residual material, four washing containers or alluvial fans were opened in an East-West direction that facilitated their dumping into the river.

The work: The process would consist of directing the water from the mine face through some river beds made manually, dragging the rocks and clay. The action of the miners' picks, which would be placed either on the side of the stream or inside it, would do the rest.

Agogae: They are the pits made in the ground area of the mine to which the water coming from the head of the farm stops. Before the mud swept by the water entered the agogas ( channels for drawing off water) the thicker boulders were removed, which the miners deposited in heaps aligned along the sides of the canals, in areas that had already been mined. Those piles of rocks are called "murias".

Canal of wood: To retain the gold dust, heather was used in a channel through which water flowed with minerals. Plinio says that "the ulex, after drying, burns and its ash is washed by placing it under a bed of grass so that the gold can be felt there". Having a higher density, the gold was deposited in the bottom of the channel, where it was retained by the leaves of heather.

The name of the mine comes from the word "Erase" (lat. Burra), synonym of sediment, waste, in reference to the material left over from the mine.

SETTLEMENTS IN THE AREA OF AS BORREAS

Some researchers believe that the Beneficiarius Procuratoris, together with its garrison, could reside in the village of A Vila da Sen (parish of Bembibre), located 2.5 km southwest of the As Borreas Mine. This hypothesis is based on three indications:

- The geographical proximity of the settlement to the mine and also the perfect visual domain that would exert over it and its accesses.

- The ease of communication between both sites, still retaining the remains of a path and an old way of passage: the Morteira Bridge.

- The appearance in the fort of A Vila da Sen of fragments of common Roman ceramics consisting of imitations of fountains with red-Pompeian varnish.

In order to exercise control over the network of water supply to the mine, it is believed that another garrison could be located at the settlement of A Cabeza de Seoane (Santo Adrao de Solbeira).

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

As Borreas Mine

Roman low-relief representing a group of miners Discovered near Linares (Jaén) in 1875

Slate with the mark of the VII Legion